- Home

- Antonia Fraser

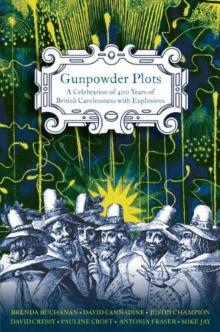

Gunpowder Plots: A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night

Gunpowder Plots: A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night Read online

Gunpowder Plots

Gunpowder Plots

BRENDA BUCHANAN

DAVID CANNADINE

JUSTIN CHAMPION

DAVID CRESSY

PAULINE CROFT

ANTONIA FRASER

MIKE JAY

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

ALLEN LANE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 3YZ (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany,

Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2005

1

‘The Fifth of November Remembered and Forgotten’ copyright © David Cannadine, 2005;

‘The Gunpowder Plot Fails’ copyright © Pauline Croft, 2005; ‘The Gunpowder Plot Succeeds’

copyright © Antonia Fraser, 2004, first published in What Might Have Been, edited by

Andrew Roberts; ‘Four Hundred Years of Festivities’ copyright © David Cressy, 1992,

first published in Myths of the English, edited by Roy Porter; ‘Popes and Guys and

Anti-Catholicism’ copyright © Justin Champion, 2005; ‘Bonfire Night in Lewes’

copyright © Mike Jay, 2005; ‘Making Fireworks’ copyright © Brenda Buchanan, 2005

The moral right of the authors has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-14-190933-2

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction: The Fifth of November

Remembered and Forgotten

DAVID CANNADINE

1 The Gunpowder Plot Fails

PAULINE CROFT

2 The Gunpowder Plot Succeeds

ANTONIA FRASER

3 Four Hundred Years of Festivities

DAVID CRESSY

4 Popes and Guys and Anti-Catholicism

JUSTIN CHAMPION

5 Bonfire Night in Lewes

MIKE JAY

6 Making Fireworkss

BRENDA BUCHANAN

List of Illustrations

Endpapers:

‘Fireworks for the Fifth’ (Mary Evans Picture Library).

p. 4–5

‘Lloyd’s Jubilee Fireworks’ (Hagley Museum and Library).

p. 22–3

The Conspirators (Fotomas).

p. 26

Victorian image of Guy Fawkes’ arrest (Fotomas).

p. 30–31

The Execution of the Conspirators (Fotomas).

p. 35

Map showing approximate blast area if the gunpowder had successfully exploded (Information courtesy of Dr Geraint Thomas, Centre for Explosion Studies, University of Aberystwyth, map copyright © Guildhall Library, Corporation of London).

p. 50

Mid eighteenth-century image of Guy Fawkes being discovered by the eye of God (Fotomas).

p. 72

Late eighteenth-century cartoon of Charles James Fox being carried as a guy (© Guildhall Library, Corporation of London).

p. 75

Boys carrying guy through streets of London, 1834 (© Guildhall Library, Corporation of London).

p. 82–3

Lewes Bonfire Night – Pope effigy (Richard Grange/Newsquest).

p. 87

Early English Protestant anti-Catholic print showing the Pope and his priests as wolves and Protestant martyrs (Cranmer and others) as lambs (British Library).

p. 91

A detail of a print showing part of an anti-Catholic procession through the City of London in 1680, with figures on floats derisively dressed up as Jesuits, bishops and so on (British Library).

p. 94–5

A print from 1680 that manages to include every conceivable anti-Catholic libel on a single sheet (British Library).

p. 97

A heroic Cromwell tramples on error (National Portrait Gallery).

p. 114–15

Commemorating the centenary of the Armada’s destruction, this print shows the Pope’s and the Devil’s plans being thwarted by God, who both creates the storm that scatters the Spanish fleet and reveals Guy Fawkes’ planned ‘Deed of Darknesse’ (Fotomas).

p. 120

Lewes Bonfire Night (Richard Grange/Newsquest).

p. 123–4

Lewes Bonfire Night (Richard Grange/Newsquest).

p. 127

Lewes Bonfire Night (Richard Grange/Newsquest).

p. 147

Title page from Babington’s Pyrotechnia (Fotomas).

p. 155

A page from Babington’s Pyrotechnia (Fotomas).

p. 156

Catherine wheels from Pyrotechnia (Hagley Museum and Library).

p. 158–9

Babington’s George and Dragon firework construction (Hagley Museum and Library).

p. 174–5

‘The Grand Whim for Posterity to Laugh At’: the disastrous firework display in Green Park marking the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, 1749 (Fotomas).

p. 178–9

The Duke of Richmond’s display, which used up fireworks left over from the Green Park disaster (Fotomas).

p. 182–3

Fireworks marking the Peace of 1814 (Fotomas).

p. 186

American firework advertisement (Hagley Museum and Library).

p. 189

Girl holding a sparkler (Hagley Museum and Library).

INTRODUCTION

The Fifth of November Remembered and Forgotten

DAVID CANNADINE

Please to remember the Fifth of November,

Gunpowder Treason and Plot.

We know no reason why Gunpowder Treason

Should ever be forgot.

At first sight, it seems strange that across four hundred years our nation has been annually commemorating an event that did not happen: namely, the failed attempt by Guy Fawkes and his fellow Catholic conspirators to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London at the beginning of a new legislative session on 5 November 1605. They were arrested, they were tortured, they were tried and they were executed. As such, they shared the fate of many conspirators who are labelled freedom fig

hters by their supporters, or derided as rebels and anarchists by their opponents, and who get caught by the very authorities they seek to overthrow. They lose, they suffer, they die, and their story ends, while the regime endures that they vainly sought to change. To be sure, the stakes were very high in November 1605: if the gunpowder had exploded, the entire Commons and Lords, plus King James I and his court, would have been blown to oblivion, in a destructive carnage that might have surpassed that of 9/11 in terms of numbers killed, and would certainly have exceeded it in terms of the collective might and power of those who had been taken out. Put in the Bush-and-Blair language of our own day, the foiling of the Gunpowder Plot was thus an outstandingly successful pre-emptive strike against what would now be described as the forces of organized, fanatical, religiously motivated terrorism.

But is this sufficient to explain why (and how) Guy Fawkes and his co-conspirators have enjoyed four centuries of demonized immortality, rather than of ignominious oblivion? It seems unlikely, for during that period, England’s ritual calendar of commemorative events has been constantly evolving and transformed, and many once-secure festivals, commemorating what seemed to be important (indeed, iconic) national events, have subsequently fallen away: among them Armada Day, Oak Apple Day, Waterloo Day, Primrose Day, Empire Day, and so on. To be sure, Remembrance Day was successfully invented after the First World War, and it is still going strong; but it is not yet a hundred years old, and it may not survive the passing of the present queen’s reign. Thus regarded, the Fifth of November is the only major date, not directly derived from the lifecycle of Jesus Christ, which has endured in our popular national calendar for so long. It is, then, an occasion easily taken for granted, but also in need of historical explanation and analysis. The essays gathered here attempt to do just that, and in so doing, they demonstrate how it has survived and evolved across the centuries, and what has been remembered (and forgotten) during the course of that survival and evolution; and they also make plain what a many-sided and multifaceted occasion it has almost always been.

As Pauline Croft explains, the genesis of the Gunpowder Plot must be sought in the complex mixture of hopes and anxieties with which English Catholics greeted the accession of James I on the death of Queen Elizabeth in March 1603. Initially, it seemed as though the new king would treat his Catholic subjects with more kindly tolerance than his predecessor, but within little more than a year these anticipations had been disappointed. To a small group of committed Catholic conspirators, of whom Guy Fawkes was one, the only way forward now seemed to be to assassinate the king, and to proclaim his daughter Princess Elizabeth as (they hoped) a more malleable and pro-Catholic queen. What would have happened had they succeeded? Antonia Fraser’s imaginative essay in counter-factual history seeks to answer just that question, opening as it does with the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II (as the nominally Catholic Princess Elizabeth had now become) on 15 January 1606. Meanwhile, her surviving brother, Charles, who was nominally Protestant, had fled to Scotland, where he had been proclaimed king. Eventually, Catholic England and Protestant Scotland might well have gone to war, Charles might still have lost his head, a Catholic, pro-French monarchy would have been established in England, and the Fifth of November would have been celebrated as a very different sort of occasion from that with which later generations have been familiar.

But the plot failed, and as David Cressy points out, the Fifth of November subsequently became the most enduring anniversary in the nation’s Protestant calendar, taking on different meanings, and attracting the support of different groups, at different times, and for different purposes. During the seventeenth century, it was a Protestant celebration of providential deliverance, often enjoying both elite and popular involvement. Under the Hanoverians, elite observance was more dutiful than enthusiastic, while among the lower orders it became an occasion for riot, disturbance and displays of misrule which lasted well into the nineteenth century. Only at the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, and on into the early twentieth century, did bonfires and fireworks become more respectable, with more children participating, and with shouts of ‘penny for

the Guy’. But despite these changes, there was, throughout, an underlying theme of militant, national Protestantism, which was always the key to its survival. Put the other way, as Justin Champion reminds us, this meant that the Fifth of November has always been an explicitly or latently anti-Catholic event: indeed, for well over the first hundred years of its existence, it was the Pope who was burned in effigy, and it was only in the late eighteenth century that Guy Fawkes became the central figure who was now consigned to the flames.

These national changes and developments are vividly illuminated in Mike Jay’s essay, which explores Bonfire Night in Lewes, a generally quaint and quiet market town in East Sussex, where the observances retain much of the riotous and oppositional character by which they have been characterized since the late eighteenth century. For reasons that are not wholly clear, the town remains to this day a ‘strong citadel of Bonfiredom’, and for this one night only it combines civic pride and civic disobedience in a particularly resonant combination: in addition to Guy Fawkes, other figures recently burned in effigy have included Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, John Major and Gordon Brown. But the Fifth of November needs to be understood not only in local but also in global terms, and this is the purpose of Brenda Buchanan’s concluding contribution. Fireworks and Bonfire Night are inextricably linked in the popular mind; but as she explains, this was not a pre-ordained union. Getting gunpowder from China to England was a complex and protracted business; and thereafter fireworks were more broadly associated with military triumphs, royal occasions and civic ceremonial. Only in the late nineteenth century did they become the indispensable accompaniment to the Fifth of November itself.

All of which is simply to say that the history of Bonfire Night is a long, complex, changing and contested one, which has rarely received the attention that it merits, and which may be approached in a variety of (not always compatible) ways. From one perspective, that history may be regarded as a consensual display of shared national values, collective identity and religious moderation; from another, it can be seen as a sustained display of establishment exclusiveness, national xenophobia and religious bigotry; from yet a third it can be looked at as a sign of vigorous popular protest, committed radical politics and technological cosmopolitanism. There are thus many narratives of the Fifth of November, and they do not all lead to the same conclusions. That, in turn, may help to explain its unique longevity: it has meant many things to many people in many places at many times. Nor is that history over yet. In recent years the growing concern about terrorism and about health and safety, the decline in a shared sense of national and Protestant identity, and the alternative, American allure of Hallowe’en, have led some to fear that the Fifth of November is on the way out. But such anxieties have often been expressed across the four hundred years since 1605, and they have never yet been borne out.

Are things different in 2005? How will Guy Fawkes Night look in 2010? If the varied, disputed, unpredictable history of this event is any guide, then it is impossible to predict how it will evolve in the future. As the bonfires burn, the fireworks fizzle and the sparklers sparkle in this anniversary year, they may seem the dying embers of an outmoded festival that no longer resonates in the secular, multicultural, globalized world we now inhabit, where the old national identities, built around (among other things) royalty and religion, have lost some of the significance they once had. But it may be, in an era when many Britons are hostile to ‘Europe’, with (as they see it) its historic and alien connotations of Catholicism and authoritarianism, and when others are no less opposed to what they regard (and regret) as the Americanization of our culture, of which the recent rise of Hallowe’en is but one more disturbing sign, that the Fifth of November will take on a new identity as a focus for protest against our nation’s precarious position, increasingly threatened by two powerful (and predatory?)

continents. ‘Guy Fawkes for UKIP’ may not seem a wholly plausible slogan. But stranger things have happened during this remarkably long-lived festival of fun and fire, playfulness and patriotism, inclusion and exclusion. Only time will tell.

CHAPTER ONE

The Gunpowder Plot Fails

PAULINE CROFT

On 9 November 1605, four days after the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot only hours before the state opening of Parliament, the shaken members of the House of Lords and the House of Commons were sent home. The government of James I wanted to concentrate on pursuing the terrorists and bringing them to justice, without the additional distractions of managing a parliamentary session. On 21 January 1606, after a lengthy Christmas break, the Lords and Commons reconvened. The prolonged holiday had done little to lessen the general sense of shock. Both Houses were still stunned by the near-miss of the planned atrocity which would have killed and maimed so many of their members. As the Attorney General, the great lawyer Sir Edward Coke, commented sombrely: ‘No Man can aggravate [exaggerate] the Powder Treason. To tell it, and know it, is enough.’ Coke’s words point to the immediate impact of the plot and help to explain its enduring place in British historical consciousness. However, ‘to tell it, and know it’ we must begin much earlier.

By 1590 Queen Elizabeth, born in 1533, had lived longer than either her father or her grandfather, and her subjects were ever more aware that her days were numbered. North of the Border, James VI of Scotland was manoeuvring energetically to maximize his chances of succeeding to her throne. James was the queen’s nearest blood relative, like her a direct descendant of the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII. After his birth in June 1566 his mother Mary Queen of Scots had publicly hoped that he would be the first ruler to unite the kingdoms of England and Scotland. Elizabeth granted a pension to the impecunious Scottish king in 1586 and promised that she would not undercut any right or title that he possessed. Further than that she would not go. As the years passed James became increasingly agitated that he had never been officially proclaimed her heir.

Warrior Queens

Warrior Queens The Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot Cromwell

Cromwell The Weaker Vessel: Women's Lot in Seventeenth-Century England

The Weaker Vessel: Women's Lot in Seventeenth-Century England Marie Antoinette: The Journey

Marie Antoinette: The Journey Oxford Blood

Oxford Blood Your Royal Hostage

Your Royal Hostage Cool Repentance

Cool Repentance Mary Queen of Scots

Mary Queen of Scots Political Death

Political Death Royal Charles: Charles II and the Restoration

Royal Charles: Charles II and the Restoration My History: A Memoir of Growing Up

My History: A Memoir of Growing Up Perilous Question: Reform or Revolution? Britain on the Brink, 1832

Perilous Question: Reform or Revolution? Britain on the Brink, 1832 Jemima Shore at the Sunny Grave

Jemima Shore at the Sunny Grave A Splash of Red

A Splash of Red Must You Go?: My Life With Harold Pinter

Must You Go?: My Life With Harold Pinter Love and Louis XIV: The Women in the Life of the Sun King

Love and Louis XIV: The Women in the Life of the Sun King The Warrior Queens

The Warrior Queens The Wild Island

The Wild Island Quiet as a Nun

Quiet as a Nun Perilous Question

Perilous Question Cromwell, the Lord Protector

Cromwell, the Lord Protector Gunpowder Plots

Gunpowder Plots The Wild Island - Jemima Shore 02

The Wild Island - Jemima Shore 02 Gunpowder Plots: A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night

Gunpowder Plots: A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night Gunpowder Plots_A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night

Gunpowder Plots_A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Must You Go?

Must You Go? My History

My History